The bond between father, son, and locomotive spans generations in this story written by former railroad historical society president Dan Lynch for the Journal Gazette in June, 1990.

The news that Comiskey Park in Chicago is to be torn down made me realize just how long ago I was last there.

Sometime in the late 1950s is my best guess, but I recall it for it was my father who took me there to see the White Sox, his favorite team. This man, so close to be for the better part of 40 odd years, was an elegantly simple human being of a few pleasures, unassuming, unpretentious, and just a little shy. At just under six feet, he was my friendly giant, for I looked up to him in every way.

By the time I was born in 1946, nearly a half century of his life had come and gone. His hair had worried into a soft gray, but everyone still called him Red. Red Lynch, the roundhouse foreman. His given name was Lawrence. I called him Dad.

One of three sons of an Irish immigrant coal miner, he was born in Powhatan, West Virginia in 1889. One brother, Joe was itinerant. The other, Terrance, worked in the mine. He had three sisters. Mary was a nurse. Agnes and Ceal married eastern money and lived in fine old Victorian homes on hills with cooks and servants.

Somehow, Lawrence ended up in Chicago in the law 1920s, and began his long career as a machinist for the New York Central System, an 11,000 mile rail dynasty. Its most famous train was the celebrated Twentieth Century Limited; 16 and one half hours, New York to Chicago, all first class. He was proud of his railroad. They made him a supervisor in 1940.

This was the man who carried me on his shoulders countless nights until I had fallen asleep. This was the man I startled when, at age two, I plucked the lighted cigar from his mouth and placed it squarely into my own. This was the man who fostered my interests, coached my Little League team, bought me toys, gave me money, lent me his car and moderated disputes between my mother and me. Always so much older than the other kid’s dads, he was more of the nature and disposition of a kindly old grandfather. He was my best friend.

His were the best milkshakes in the whole world. Two of his favorite TV programs, “Gunsmoke” and “The Untouchables,” became my favorites. Three of his four cars when I was growing up were Studebakers, but he let me talk him into a Chevrolet. I didn’t have the biggest Lionel train on the block, but I had the services of a full-time railroad consultant to keep it running. Railroad men from the first half of the century all share a common look, that of a worried scowl ranging from just more than noticeable to severe. His was fairly benign, but it was evident that not far in the back of his mind a telephone was always ringing in the middle of the night with the news that a train had wrecked.

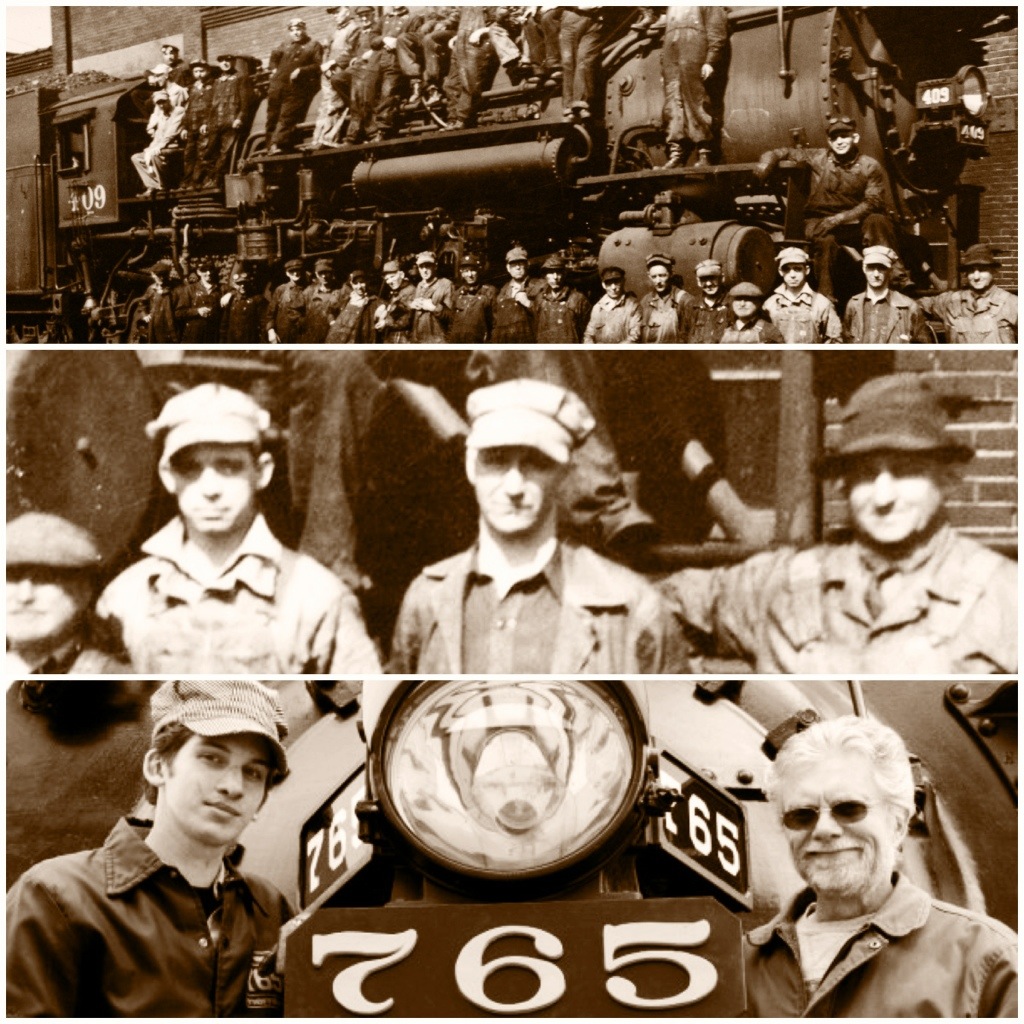

The first time he shared that part of his life with me remains a series of spectacular mental photographs that I now use as bedtime stories for my son, Kelly, who is approaching the age I was when my dad took me to the roundhouse with him long ago.

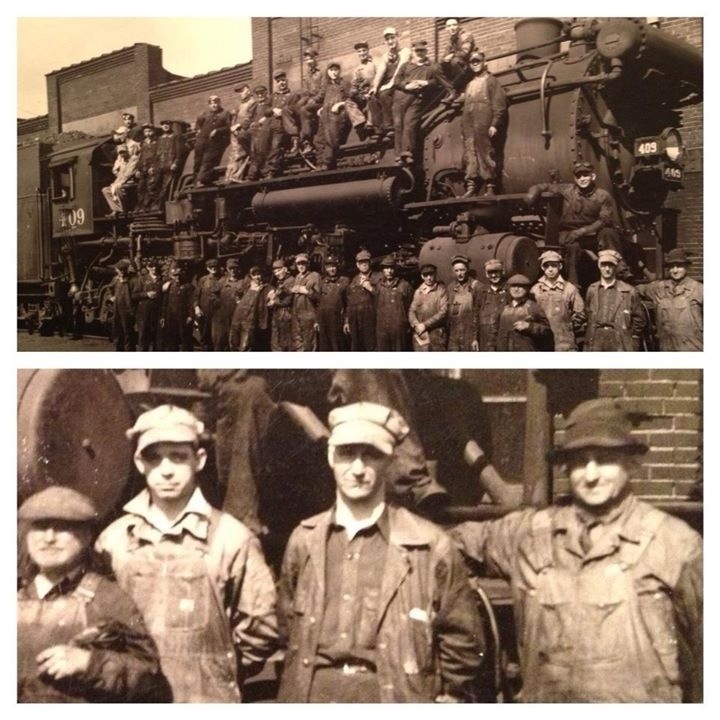

The Indiana Harbor Belt roundhouse in Hammond, near the town line of East Chicago, was an enormous, semicircular red brick building with vast windows so layered in soot as to obscure even the most intense sunlight. To railroad people, this was Gibson, and it was there that the steam locomotives of the IHB and its parent New York Central were given new leases on the charmed lives of railway engines by craftsman who had just won the last great war. Some of the men, just in for their day in their crisp Oshkoshes, stood out like cartoon characters against the dusty patina of heavy industry. Others, blackened by their tasks, moved about with huge tools. Red Lynch was not just another supervisor. He was one of the good guys. He was the guy you hoped would be your boss.

He introduced me to several men, and I watched them work. Welders and torches flickered and sparked. The smell of coal smoke, bearing grease and steam filled the caverns with a roar of a dozen machines all trying to talk at once. His cinder block office near the showers and the nickel Coke machine was spartan. There, records were kept, written in longhand in great ledgers by men who could wield a fountain pain as eloquently as any tool. Outside, just beyond the turntable where the engines were spun around to face their work, we found a locomotive simmering idle on a track that lead to the coaling tower. Once up in the cab, dad threw a few shovels of coal into the firebox and checked the water level. He held me up so I could reach the whistle cord, and I signaled it for a move. It was the loudest sound I’d ever heard.

We spent the afternoon, his day off, on that engine riding up and back. It was a day of complete fulfillment of nearly every boy’s dream to have a train, a real train, all his very own. But it was more than just one of many memorable outings with my dad. He knew what he was doing; dads know everything. He had taken me to the edge of the canyon to mingle with the great dinosaurs in their moment before extinction. It was 1953, and the diesels were on order.

At age 5, and having fun as never before, I failed to comprehend the significance of the moment. Puff the Magic Dragon was about to be slain, and I got his autograph. I heard him speak and watched his final performance from the best chair in the house; my dad’s lap in the engineer’s seat. “Look, Ma, top o’ the world!”

When my dad retired in 1962, the New York Central gave him a piece of paper that read, “In recognition,” a tie tack with the company oval and a pension that my mother would draw upon for a quarter century more. With his life’s work behind him, he became vague and a little depressed. As a teenager, I was too absorbed by the trappings of high school to realize he was growing increasingly unhappy. He lost interest in nearly everything except me. His mind wandered, and he was given to taking long drives anywhere by himself. On one such day, I watched as he backed the car out and disappeared down Greenwood Avenue. I never saw him again. Perhaps absorbed by his thoughts, he missed a turn and struck a tree. We buried him in a small family plot on a hillside in Bluefield, West Virginia, not far from his birth place.

I was damn lucky to have known him. Lawrence wasn’t even a blood relative. He fathered no children of his own, yet he embraced me as his son, and never was I given the impression that he would have done otherwise. My real father slipped away shortly before I was born; vanished to California and failed to return. He’s still there, as far as anyone knows or cares. For a short time, I knew him. He shared nothing with me, left no lingering positive impression, proving once again that anyone can be a father, but it takes an extraordinary man to be a dad.

Dan Lynch worked for over 20 years as an editorial cartoonist until a stroke sidelined him in 2001. He was heavily involved with the 765 in the 1970s and early 1980s. His son Kelly serves on the society’s board as Communications Manager and is part of the locomotive crew.

Lawrence “Red” Lynch at middle-center, his son Dan at lower right and Kelly at lower left.